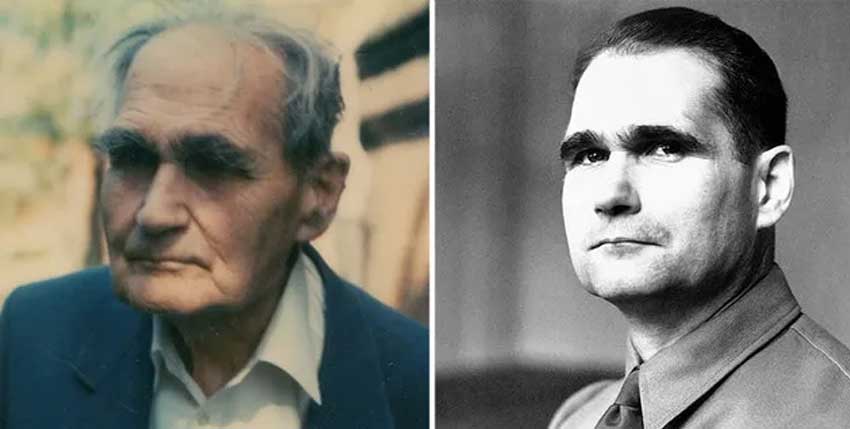

Main Image: Rudolf Hess photographed in his cell at Spandau Prison approx. 1986.

The following article is reproduced with kind permission of the website https://jailingopinions.com/realhistory/ and Heritage & Destiny magazine. Links for both the website and the magazine appear at the bottom of the page.

Recently released British government files take us a step closer to solving the mystery of the “suicide” or murder of 93-year-old Rudolf Hess on 17th August 1987.

By the time of his death at Spandau Prison, Berlin – where he was the last remaining prisoner – Hess had been in captivity for more than forty-six years, after he parachuted into Scotland on a peace mission in May 1941. Then aged forty-seven, Hess had been Deputy Führer of Germany ever since Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933.

Some of the newly released documents cast further suspicion on Tony Jordan, the black American prison guard who was named some years ago by British historian David Irving as having murdered Hess. Irving’s information came from an interview with a Berlin prosecutor, but his conclusions are now additionally supported by documentary evidence, some of which is quoted for the first time in this article.

Hess’s nurse was the Tunisian-born, German-educated Abdallah Melaouhi, who had held this post for three years and became a trusted confidant of the former Deputy Führer, due to his efficient and helpful conduct and because Hess (who was born in Egypt) was able to converse with him in Arabic.

On the morning of 17th August, Melaouhi attended to Hess’s morning exercises and medical tests in the usual manner, before going for his own lunch break. He was summoned from this lunch break some time after 2 p.m. and returned to the prison, which was by now in a state of emergency after Hess had been found dead or dying.

Hess’s usual habit after his lunch was to walk in the prison grounds, where he would sit in a “summer house” (actually a Portakabin), reading or dozing. When Melaouhi reached this summer house, he later stated “it looked as if there had been a wrestling match. …The seat on which Hess usually sat was overturned and was a long way from its usual position. Hess himself was lying lifeless on the ground: he showed no reaction. There was no measurable breathing, pulse or heartbeat. I thought he must have been dead for about 30 to 40 minutes.”

The words above come from a newly released copy of an affidavit by Melaouhi dated January 1989, though similar statements by him have long been in the public domain. What is being reported here for the first time are further specific allegations that Melaouhi makes in his affidavit about Tony Jordan, a black American prison warder.

Spandau was a unique prison, under the joint control of the four Allied powers of 1945 – the UK, USA, Soviet Union and France (even though these ceased to be “Allies” and became Cold War rivals more then forty years before Hess’s death!). There were four Governors representing each of these Allies, and four sets of prison warders.

At any given time one of these “Allies” was responsible for a garrison of soldiers guarding the prison, but these soldiers were not allowed to have any contact with the prisoner. They guarded the perimeter and did not set foot in the prison itself, which during each shift was run by three warders of different nationality: a Chief Warder, a cell block warder (who would be directly supervising the prisoner), and a warder on gate duty.

August 1987 was a month when the American garrison was on duty. On the afternoon of Hess’s death, the gate warder was British, the chief warder was French, and the cell block warder was the black American Tony Jordan.

In a January 1989 affidavit included in the newly released file, Melaouhi stated: “An American guard called Jordan treated Hess particularly unpleasantly. Hess said that ‘Hell was usually let loose’ when he was on duty.“

He did not let Hess sleep at night. He refused everything Hess asked for. He met every request with insults and abuse which were coarse and grossly offensive. Hess regularly complained about this guard and the senior American guard Ahuja was told, but nothing happened.

Then Mr Hess asked for a visit from the US Governor, Mr Keane. He made the same complaint to the Governor, in my presence. Hess was then told that Jordan was in an official post and could not be transferred. The other Governors knew about the complaints, but no action was taken.”

Melaouhi said that Hess had raised his complaint with the US General on the Allied Commission that controlled Berlin, saying that Jordan was “ill-mannered, impudent and had threatened him. He was so aggressive that he (Hess) had to appeal to the General for protection.”

These complaints were made in late April and early May 1987, just over three months before Hess’s death. Jordan was on holiday at the time, but on his return his “reaction when told about the complaint was extremely violent. He was called to see the General and at a meeting at which Governor Keane and Ahuja, the chief guard, were present, they obviously arrived at a solution which was designed ultimately to protect Jordan. Hess received a reply from the US General which more or less rejected his complaints.”

Melaouhi continued: “The guards reacted accordingly and stepped up their pressure on Hess and their harassment. As a result he became depressed. The guards were now completely refusing to allow him any assistance. Consequently Hess’s physical state declined rapidly. At the end of April or early May he told me that he was going to die or be killed or poisoned soon. He specifically asked me at that time and in that connection to let his son, Mr Wolf-Rüdiger Hess, know if that happened, but he urged me not to tell his family anything about the harassment and mistreatment while he was still alive, because he was afraid the guards would take their revenge and mistreat him even more. He said, in so many words, ‘Then we will be lost and especially me, at the age of 93.’”

On being summoned to the prison from his lunch break on 17th August, Melaouhi spoke first to Bernard Miller, the British warder on gate duty. “When I asked what was wrong, Miller said I could imagine: Jordan had been at work. The whole thing was finished and over.”

When he examined Hess’s lifeless body, the nurse recorded: “On the right side of his neck under his ear I found that there were two red pressure marks about 8cm long that looked as if they had been made by fingers. Jordan was standing near Hess’s feet and was obviously beside himself. He was sweating profusely, his shirt was soaked with sweat and he was not wearing a tie. Because of the dress and duty regulations this was unusual. I asked Jordan: ‘What have you done to him?’, whereupon he answered, in exactly these words, ‘The pig has been dealt with. You won’t need to do night duty any more.’”

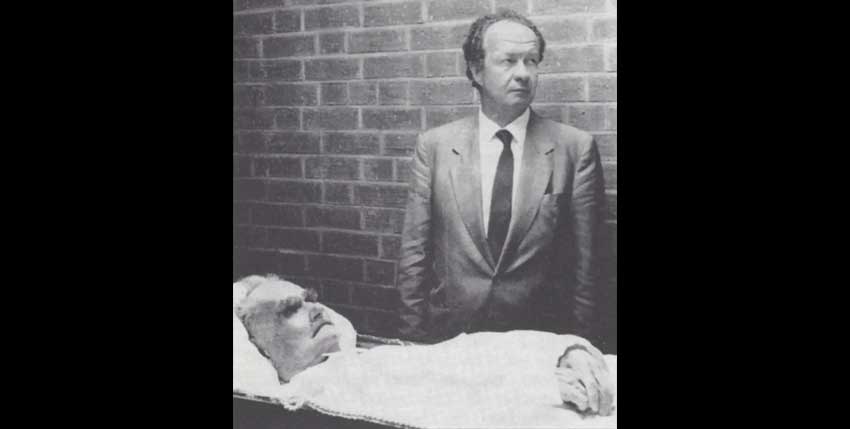

Despite the situation seeming hopeless, Melaouhi attempted resuscitation and an American soldier who had basic medical training assisted him in trying to restart Hess’s heart. He then accompanied his patient in an ambulance to the nearby British Military Hospital, where Hess was certified dead.

Within weeks, an investigation by the Special Investigations Branch of the British Military Police had concluded that Hess committed suicide, and this verdict was hastily accepted by all four “Allies”.

We should bear in mind that when Hess was sentenced to life imprisonment at the infamous Nuremberg trial, the Soviet judge had been the only dissenter – he argued that Hess should face the death penalty, but was outvoted by his British, American and French counterparts.

Exactly a month after Hess’s death, on September 17th, a British soldier from the Royal Engineers drove a bulldozer into the summer house where Spandau’s last prisoner had died. The Portakabin was smashed to pieces, petrol was poured over the remains and they were set alight. The British Governor of Spandau, Tony Le Tissier, threw into the flames the cord with which Hess had supposedly strangled himself.

When giving his sworn affidavit sixteen months later, Melaouhi was unconvinced by the suicide argument.

“Looking at the facts objectively, I think the story that he committed suicide is unlikely. The cord Hess is supposed to have strangled himself with – the only one there – was on a light and was only 70cm long. In Hess’s bedroom and bathroom there were several much longer cords which would have been much more suitable if Hess had intended to commit suicide in this way, especially the electric cord in the bathroom.

“…Hess was much more closely guarded in the summer house than in his cell. He would have been much more likely to commit suicide in the cell for that reason and also for the reason I mentioned before, that he would have had more suitable means of doing so. There does not seem to be any reason why Hess would have chosen the most unsuitable place if he intended to commit suicide.”

Regarding a supposed “farewell” or “suicide letter” in Hess’s handwriting, Melaouhi gave several reasons why he believed it could not be genuine and concluded: “I imagine the letter was forged, by an American guard who could copy Hess’s signature and must have had an interest in cooperating with the action to back up Jordan.”

It is very obvious from the files that there was indeed a concerted effort to “back up” the black American guard. His fellow warders of all four nationalities used very similar phrases to exonerate him. For example Steven Timson, a British deputy chief warder who had been on holiday when Hess died, stated that although he had heard rumours of a complaint against Jordan, he had not witnessed any such incident and “as far as I know Mr Jordan has always been polite and fair in his dealings with the prisoner”.

Timson had very good reasons not to rock the boat. A year earlier he had stolen various personal items belonging to Hess that were supposedly held securely at Spandau, including the uniform that Hess wore during his 1941 flight to Scotland. Eventually Timson was arrested after demanding 500,000 Deutschmarks from Hess’s son Wolf-Rüdiger for return of the items, but it’s significant that when the disappearance of these items was investigated in 1986 – by the Military Police Special Investigation Branch, the same force that was to investigate Hess’s death – they were unable to make any headway. The same wall of silence from Timson’s fellow warders blocked the theft investigation in 1986, just as it protected Jordan in 1987.

As with all ‘eye-witness’ testimonies, we are obliged to examine Melaouhi’s statements with due scepticism. It doesn’t help his case – though for the reasons given below it is very understandable – that he refused to give a detailed statement during the weeks following Hess’s death. All he was prepared to say to the investigators was to describe his qualifications and duties, and to outline what happened during the last morning of Hess’s life when he attended to his patient in the normal fashion. At that time (August-September 1987) he was unwilling to say anything at all about the afternoon’s events, and his brief initial statement says nothing at all about Jordan. When pressed at that time, Melaouhi stonewalled: “I am not willing to state anything further.”

It also doesn’t help that later statements and embellishments have been selectively quoted by conspiracy theorists, eager to promote an unlikely and otherwise unsupportable tale that British assassins had disguised themselves in American uniforms and smuggled themselves into the jail to kill Hess.

Such theories are built on an undocumented assumption that Gorbachev’s Soviet Union was in 1987 preparing to abandon its longstanding objection to Hess’s release on compassionate grounds, and that the British secret state (having previously relied on Soviet intransigence) decided to kill Hess so as to prevent him revealing secret wartime discussions.

As discussed in greater detail on my blog at www.jailingopinions.com/realhistory newly released documents reveal that British Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington put pressure on the other “Allies” during 1981-82 to change the previous policy (insisted on by the Soviet Union) that whenever Hess died his body should be cremated without reference to his family. such an instant cremation would of course have aided any murder plot, but there is no doubt that Carrington (seen for other reasons by Israel as hostile to the Zionist state) was the main advocate of changing the policy and allowing Hess’ body to be given to his family.

Though Melaouhi didn’t recognise some young American soldiers who were on the scene by the time of his arrival at the summer house, this is unsurprising. As explained earlier, the military garrison was kept completely separate from the prison block: soldiers of all four nationalities were strictly forbidden from entering that area or having any contact with the prisoner. Newly released documents disclose the identities of these young American soldiers, and make clear that they had answered an emergency call from the French chief warder that afternoon when Hess had been discovered dead or dying.

Other newly released documents point to a much more likely course of events than the fantasy of an assassination by British secret agents. In conversation with Melaouhi, whom he had come to regard as a trusted confidant, Hess had specifically warned against pursuing the complaints further or mentioning them to his family, saying that the other warders would take Jordan’s side and then “we will be lost and especially me, at the age of 93”. Note the word “we”: Hess was well aware that Melaouhi, as a Tunisian, would have no powerful friends or allies in Berlin.

So when the worst happened, Melaouhi could see that Jordan’s fellow Americans would protect him. He refused to join in this cover up and give the sort of pro-Jordan cover story that other ‘witnesses’ parroted, but he could see no point in recording his own story, until some sixteen months later he learned that Hess’s family had sought a second autopsy.

While dismissing the likelihood of Hess having committed suicide in the summer house, Melaouhi speculated in his January 1989 affidavit: “I think from remarks that Hess made and from my own observation that Jordan had stolen some books from Hess. That might have led to a quarrel.”

Peter Rushton, Manchester, England.

To be continued……

Foot note: This article was first published in the July-August 2022 issue #109 of Heritage and Destiny magazine, to who we give full acknowledgements. For a sample copy of Heritage & Destiny magazine please write to; H&D, 40 Birkett Drive, Preston, PR2 6HE, or check out the Heritage & Destiny website here>>

The British Movement would love to receive articles for possible inclusion on this site from members and supporters across the North of England. Please remember that we have to operate within the laws of this country – we will not include any content that is against the current laws of the United Kingdom. News reports should be topical and be relevant to the regions covered by this website.